Thank you to all who attended last weekend’s performance of Gilbert vs. Sullivan. We are thrilled to be presenting live entertainment again!

Month: January 2021

Opera Tampa Cast Week – Gilbert vs. Sullivan

In just a few days we will be kicking off our season with Gilbert vs. Sullivan! This week we will be highlighting some of our amazing cast

Gilbert vs. Sullivan costumes

Aren’t these costumes beautiful? ![]() Get ready for opera this weekend with Gilbert vs. Sullivan on the Riverwalk stage!

Get ready for opera this weekend with Gilbert vs. Sullivan on the Riverwalk stage!

Costumes by Wardrobe Witchery.

Carpet Clash Kills Cash Cow Collaboration of Gilbert And Sullivan

One of the greatest partnerships in musical theater was gravely wounded by a fight about carpet.

What a shaggy predicament.

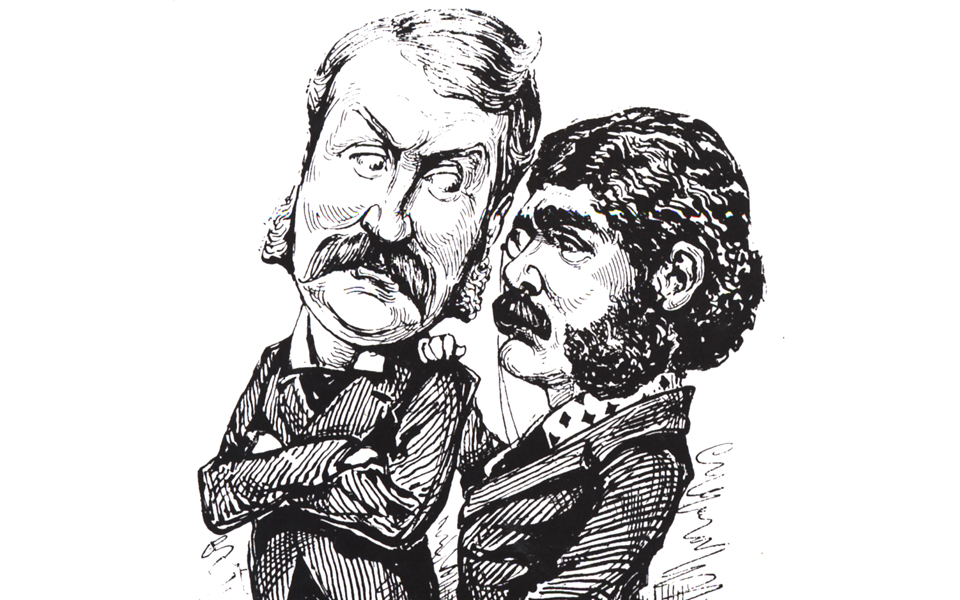

The duo of librettist W.S. Gilbert and composer Sir Arthur Sullivan was a collaboration that lasted a quarter century, creating a body of work, according to some scholars, second only to William Shakespeare.

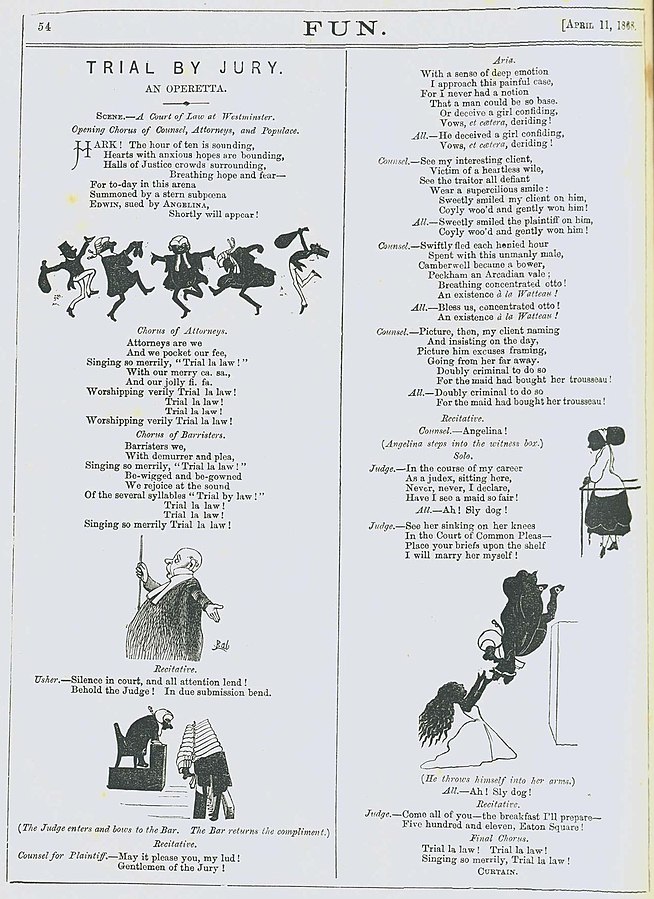

Each were successful in their respective fields before Richard D’Oyly Carte, manager of London’s Royalty Theatre, brought them together to create Trial by Jury, which spoofs the legal profession. This collaboration proved to be a hit, and demand for similar works bonded the two.

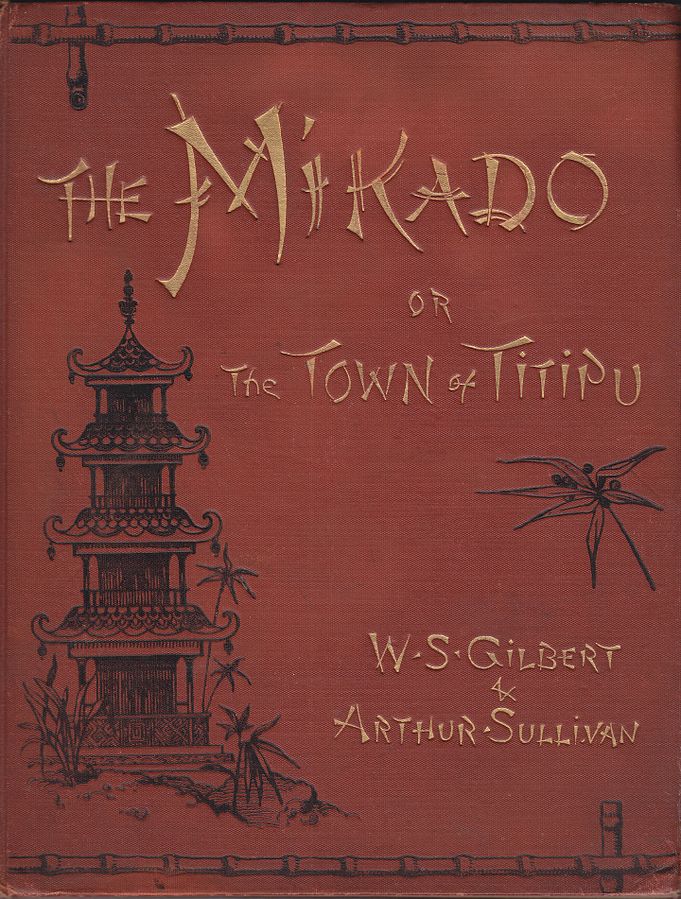

In the late 1800s, Gilbert and Sullivan wrote 14 comic operas, also known as operettas, with The Pirates of Penzance, H.M.S Pinafore and The Mikado being their best known. Music from those works will be featured in Opera Tampa’s Gilbert vs. Sullivan playing The Straz’s Riverwalk Stage Jan. 22-24.

The pair’s “topsy-turvy” operettas were always imaginative, fun and a tad absurd. Where else but in a Gilbert and Sullivan production would gondoliers end up as monarchs and pirates won’t rob ship carrying orphans because they themselves are orphans, so when word gets out, every ship they encounter purposely has orphans aboard. Foiled!

Much of their work’s humor comes from their “patter songs,” a gymnastic run of words and music where consonants and vowels quickly tumble end-over-end in a riotous and rapturous repartee. The most popular example of this is their song “I Am the Very Model of a Modern Major-General,” from The Pirates of Penzance.

The tongue-twisting lyrics: “I’m very good at integral and differential calculus; I know the scientific names of beings animalculous: In short, in matters vegetable, animal, and mineral, I am the very model of a modern Major-General,” sung at break-tongue speed is regarded as one of the most challenging patter songs ever written, according to Genius.com. Hamilton’s creator Lin-Manuel Miranda may have something to say – quickly – about that.

Despite their success, the musical marriage became strained by the repetitiveness of their work and choice of topic. Sullivan was tired of working with Gilbert, because he felt every opera was the same story of a world turned on its head, hence their “topsy-turvy” label and he wanted more realism and emotions in their work. Another rub was Gilbert continuous poking fun at the privileged class, which Sullivan yearned to be a part. Sullivan asked to leave the partnership, but the two found a way to continue by taking brief breaks, two or three months, away from each other.

After one of these breaks, in 1885, they wrote one of their most successful operettas The Mikado, which made fun of English bureaucracy that was thinly veiled by setting it in Japan. Originally, Gilbert proposed the story include a “magic” lozenge plot device that would alter the characters’ personality, that Sullivan rejected, reminding them why they sought time apart. Their creative conflict during this period was chronicled in the 1999 British film Topsy-Turvy starring Jim Broadbent and Allan Corduner.

The Mikado was the partnership’s longest running show, having 672 performances at The Savoy Theatre, a stately building constructed in 1881 by Carte to showcase their work, spawning the term “Savoy opera,” which strongly influenced the creation of the modern musical.

In 1890, the nearly fatal bump in the partner’s relationship, dubbed “The Great Carpet Quarrel,” occurred during “peace talks” arranged by Carte. Gilbert, hurt by Sullivan’s indifference, wrote a letter saying: “The time for putting an end to our collaboration has at last arrived … I am writing a letter to Carte giving him notice that he is not to produce or perform any of my libretti after Christmas 1890. In point of fact, after the withdrawal of The Gondoliers, our united work will be heard in public no more.”

The reconciliation talks went south when Gilbert challenged Carte over expenses of The Gondoliers, which included the purchase of a new carpet for The Savoy lobby, costing £500 approximately $700, based on current currency exchange. Gilbert accused the theater manager of exploitation and robbery. Sullivan sided with Carte in the dispute prompting the librettist to storm from the meeting calling the two of them “blackguards,” men who behave in dishonorable way. Gilbert sued seeking his share of net profits and his case was heard by England’s high court. Carte eventually paid Gilbert about $1,400 but the machinations of the court case including the carpet clash unraveled the friendship and partnership.

The split lasted about three years before the two were brought back together by The Savoy’s music publicist. They wrote two more operaettas, Utopia, Limited (1893), a moderate success, and The Grand Duke (1896), a complete flop and the final nail in the coffin of their musical union.

Sullivan died in 1900 and Gilbert died in 1911.

Nightly Met Opera Streams

This week of free Nightly Met Opera Streams pays tribute to the inimitable artistry of soprano Renée Fleming, with screenings of some of her most memorable Met portrayals—from the Countess in Le Nozze di Figaro to the Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier and the title heroines of Armida, Rodelinda, and Rusalka.

Throw back Thursday to Home for the Holidays

#TBT to our Home for the Holidays performance a few weeks ago! Were you there?